Meander – Yakety Yak, handmade cedar kayak, bronze ornament, 2014.

Méandre – une dérive continentale, vidéo de l’exposition au centre VU, Québec (durée : 3:15 min.), réalisation vidéo: Josiane Roberge, narration : Victoria Stanton, 2016.

Points of confluence – Eastman – Autoroute 10 / day : 01, video (1:42 min.), 2014.

Meander – Yakety Yak (detail), handmade cedar kayak, bronze ornament, 2014.

Méandre – Yakety Yak II, impression numérique, 2015.

Le chavirement des marées, kayak en cèdre, ornement en bronze, moteurs programmés et cordage, 2016.

One son one ocean, pagaie en cèdre, hauts parleurs, support en bois, aluminium et laiton, 2015.

Collaboration et narration: Victoria Stanton.

Points of confluence – McDonald Creek – Hudson River / day : 18, video (1:19 min.), 2015.

Méandre – Lac Champlain, impression numérique, 2016.

Jane Gulls Nest – Champlain lake, digital photography, 2016.

Méandre, ornement en bronze oxydé par le Fleuve Hudson et support en bois, 2016.

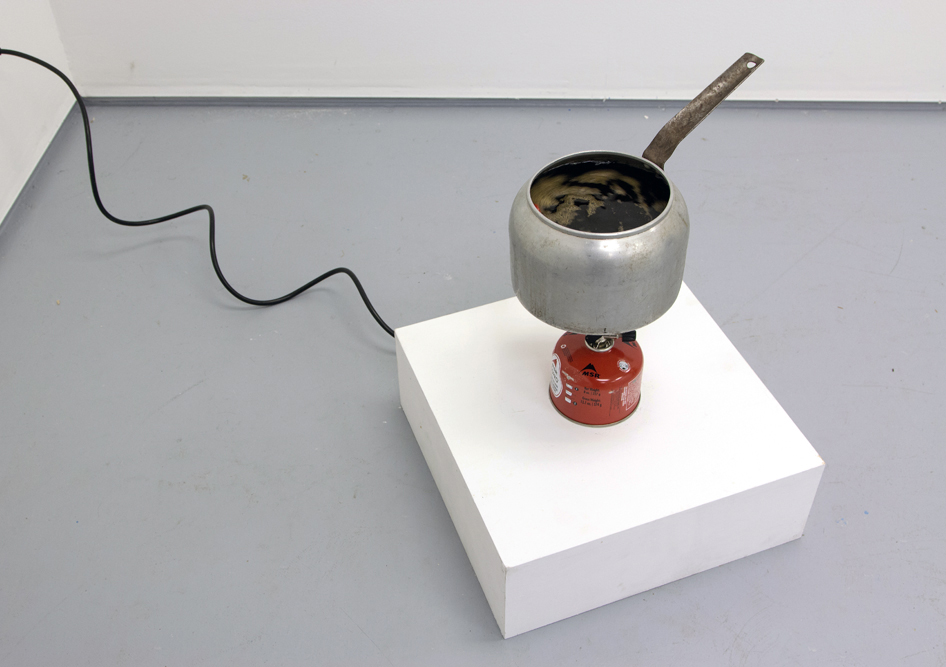

Eaux troubles, réchaud de camping à gaz, chaudron, encre de seiche, pétrole, eau et dispositif rotatif, 2016.

Points of confluence – under Manhattan bridge / day : 30, video (0:45 min.), 2015.

Chatoiements, coquille d’huitre, sable, dispositif d’éclairage animé et support en bois, aluminium et laiton, 2016.

Nuit noire, hamac et dispositif rotatif, 2015.

Meander, partial view of the exhibition at Pacific Sky Exhibition, Eugene, Oregon, U.S.A., 2015. Photos: Jack Ryan.

Points of confluence – Missisquoi South / day: 06, video (1:30 min.), 2016.

Meander :

a continental drift

On July 2014, Patrick Beaulieu embarked on a slow continental drift. Traveling by kayak he crisscrossed meanders that took him from the source of a river in southern Quebec, to the Atlantic Ocean at the mouth of the Hudson River in New York. He explored the condition of such places that can only be discovered by surrendering oneself to the contemplation of forces beyond our comprehension. Navigating through this venerable passage within the rhythms of subtle currents, he sought to visually capture these points of confluence – where the intersection of landscapes and human encounters generate poetry.

I’ll never really know how he felt.

Alone on the water.

Even when I try to imagine it, it seems abstract. Yes, I feel sensations. I’ve been on the water. But never on that water. Floating. Freestyle. Alone.

Maybe my imagination blocks me: because of my fear of being alone. Or is it my fear of deep water?

I didn’t know that I feared deep water until one day when my stepfather brought me out to the middle of the ocean, the dark blue all around and stretching out as far as the eye could see. I couldn’t feel my feet under me. I became queasy. I needed to be on dry land.

“Three years ago I was giving a workshop in the Rockies. A student came in bearing a quote from what she said was the pre-Socratic philosopher Meno. It read, “How will you go about finding that thing the nature of which is totally unknown to you?” … The student made big transparent photographs of swimmers underwater and hung them from the ceiling with the light shining through, so that to walk among them was to have the shadows of swimmers travel across your body in a space that itself came to seem aquatic and mysterious.”[1]

The word dissolution comes to mind. I didn’t think it up on my own, though it was Patrick who sprinkled this, like a light rain, in my direction. But it’s stayed with me. It’s not so much fear of deep water as it is of dissolution. What if my being dissolved – melted away, extending outward from the small skiff that my stepfather navigated – merely by looking at the rippling surface beneath?

“The question the student carried struck me as the basic tactical question in life. The things we want are transformative, and we don’t know or only think we know what is on the other side of that transformation. Love, wisdom, grace, inspiration – how do you go about finding these things that are in some ways about extending the boundaries of the self into unknown territory, about becoming someone else?”[2]

Patrick spoke of dissolution as a kind of freedom. A dilution of his body, an absorption into his surroundings. A surrender. A terrifying beauty. An endless unknown. For Patrick, it wasn’t so much about becoming someone else, another human – but about becoming another body; a body of water. As a drop of water going from the river into the ocean.

“All rivers flow into the sea, but does the sea turn back their waters? The currents of hardship pour into the sea of the Lotus Sutra and rush against its votary. The river is not rejected by the ocean; nor does the votary reject suffering. Were it not for the flowing rivers, there would be no sea.”[3]

As a drop of water, going from the river into the ocean. I try to imagine the challenges he faced; to picture the kinds of dreams that filled his nights when he wasn’t paddling across the currents. Watery dreams of sunlight and tributaries, drifting in and out of consciousness, a body of half-sleep.

The works that have materialized (installations, videos, photographs) following this performative journey, this continental drift, contain and evoke that which does not dissolve completely.

And so what you see here are the traces. The journey itself can only ever be lived by the person who lived it, by one person at a time. Deep waters filling our collective unconscious, we’re alone on our journey: Patrick’s journey, your journey, and mine.

[1] Rebecca Solnit, A Field Guide To Getting Lost, p. 4

[2] Solnit, p. 5

[3] Nichiren Daishonin, The Writings of Nichiren Daishonin, Vol. 1, p. 33

Dreams As Drops of Water of Victoria Stanton, Pacific Sky Exhibition, Eugene, Oregon, 2015.

In 2014, Patrick Beaulieu, whose “performative trajectories” have led him to follow the American winds (Ventury, 2010) and the migration of monarch butterflies (Monarch Vector, 2007), embarked on a poetic meandering voyage in his handmade cedar kayak. Beaulieu surrendered to the ebbs and flows of the world by drifting from the source of the Missisquoi river in Quebec to the mouth of the Hudson River in New York.

While submarines and cargo ships map out their trajectories with electronic navigation devices and complex passage planning, Beaulieu’s Meander embraced slowness and loss of control and followed the fluid current that runs between seemingly stable land masses. The artist chose to follow the Missisquoi river due to the water current’s slowness and the fact that the body of water has a history of being used as a navigation tool by First Nations peoples. Beaulieu spent 30 days drifting on the sky-dyed waters, stopping to hang his hammock for the night. Following the water’s current, the artist found contentment in the slowness and the state of abandon with which he navigated as the journey allowed for a meditative experience and an exercise of attention.

Floating on the water and renouncing volition, certainty and action, Beaulieu’s trip threatened to slowly erode the seemingly stable ideas we have of freedom, self, and space. Surrendering to the forces of nature, Beaulieu’s Meander embraced a particular kind of passivity and non-action that gives rise to new definitions and experiences of freedom. Indeed, the artist’s absurd voyage echoes Albert Camus’s idea that freedom can only exist in the recognition of the absurdity of existence, in recognizing that the current will take you where it wants to. By accepting the possibility of tipping over and loosing balance, and by choosing to follow the water, Beaulieu’s Meander exercises a freedom that is in tune with the subtle currents of the world and powers greater than us.

Beaulieu’s journey may remind us of Bas Jan Ader’s 1975 transatlantic sailing voyage In Search of the Miraculous, during which the artist mysteriously vanished to a space both unmapped and irrational. Like Ader, who departed from Cape Cod with a camera and tape recorder, Beaulieu set out to record his trip with an GoPro camera. Pushed by the force of the water under his canoe, Beaulieu recorded the pace of being adrift. Relinquishing his artistic authority to the waves, Beaulieu set up a fixed camera that filmed short videos of his voyage, the sway of the canoe working to compose the images.

In his exhibition at Art Mur, Beaulieu shares his experiences through photographs, a series of short videos titled Points of Confluence, and animated sculptures that act as vestiges of his time on the water. A perpetually rocking cedar kayak, a spastic hammock, a cauldron containing a whirlpool, two whispering cedar paddles, a flashlight revealing lunar cycles, and a burnt bowl of oatmeal are among the objects exhibited.

Floating, drifting, and meandering from Quebec to New York, the artist travelled aimlessly, letting the current take him. Nonetheless, Patrick Beaulieu’s voyage was not an aimless one: as the water’s natural forces eroded the ordering concepts of departure and arrival, beginning and end, the artist’s destination was much greater than any point on a map.

– Isabelle Lynch, extract from Meander, Invitation vol 11, no 3, Art Mûr Galerie, Montreal, 2016.

[…] Les vidéos témoignent du passage de l’artiste dans des lieux transitoires qui deviennent tout à coup propices à la contemplation, au regard singulier. Elles évoquent aussi l’ancrage des êtres humains sur les rives, par exemple, sur celles de McDonald Creek. Les maisons et les RV défilent sous nos yeux, dans une lumière et un silence qui ressemblent à ceux des petites heures du matin. Le monde est endormi, mais le cours d’eau continue son mouvement vers la mer, tel que nous l’évoque son bruissement incessant. (…) Méandre comporte plusieurs strates qu’on ne peut découvrir qu’en acceptant une lenteur, celle qui est au cœur de la démarche même de l’artiste. Par cette lenteur, c’est « la vie elle-même comme ondoiement, comme déploiement » qui fait surface.

– Paule Macros, extract from Méandre, Invitation vol 11, no 3, Art Mûr Galerie, Montreal, 2016. Read the integral text

Meander project have being presented in fall 2015 at Pacific Sky Exhibition (curator : Jack Ryan), Oregon, U.S.A. and in 2016, at Art Mûr Gallery in Montreal, at VU Photo Art Center in Quebec as part of Mois Multi 2016 and at Kamouraska Art Center as part of the Rencontre photographique du Kamouraska 2016.

voice and contribution in one son, one ocean :

VICTORIA STANTON

programming and development support :

PASCAL AUDET

consultants :

LUC LOIGNON

JEAN GAGNON

sound recording (one son, one ocean) :

KINNTA / CHRISTIAN RICHER

artistic collaboration :

ESTELA LÓPEZ SOLÍS

JACK RYAN

photographic documentation :

SWANN BERTHOLIN (Montréal)

JACK RYAN (Eugene)

videographic documentation :

JOSIANE ROBERGE (Quebec)

Meander logotype design :

FEED

Meander bronze ornament:

MULTIPLE

bronze ornament production :

ROBOCUT

technical support :

JOHN FREDY RIVAS GOMEZ

DANIEL VEILLETTE

SWANN BERTHOLIN

collaboration :

PACIFIC SKY EXHIBITION (OREGON, É.U.A.)

COAST TIME (OREGON, É.U.A.)

GALERIE ART MÛR (MONTRÉAL, CANADA)

VU PHOTO (QUÉBEC, CANADA)

MOIS MULTI 2016 (QUÉBEC, CANADA)

CENTRE SAGAMIE ART ACTUEL (ALMA, CANADA)

LES TROIS GRÂCES CAFÉ BISTRO (EASTMAN, CANADA)

Meander‘s footprint is poetic rather than carbonic thanks to: carboneboreal.uqac.ca

Press

- L'art de la dérive – Patrick Beaulieu s'est laissé flotter de la Missisquoi jusqu'à New York, au fil de l'eau. (pdf) Catherine Lalonde, Le Devoir, Monday, August 10th, 2015.

- The Art of Drift - Patrick Beaulieu let himself float from the Missisquoi to New York following the water’s flow. (External link) Bora Mici, Artists Speak, translation of the article by Catherine Lalonde originally published in French on Le Devoir, Monday, August 10th, 2015.

- Dreams as drops of waters. (pdf) Victoria Stanton, Dreams as drops of waters, Pacific Sky Exhibitions, 2016.

- Invitation, volume 11, numéro 2, Galerie Art Mûr, Montréal, 2016. (pdf) Invitation, volume 11, numéro 2, Galerie Art Mûr, Montréal, 2016.